What Would Marie Tharp Do?

July 24, 2012 | Comments: 2 Comments

Categories: Feminism, Marie Tharp, Publishing, Soundings

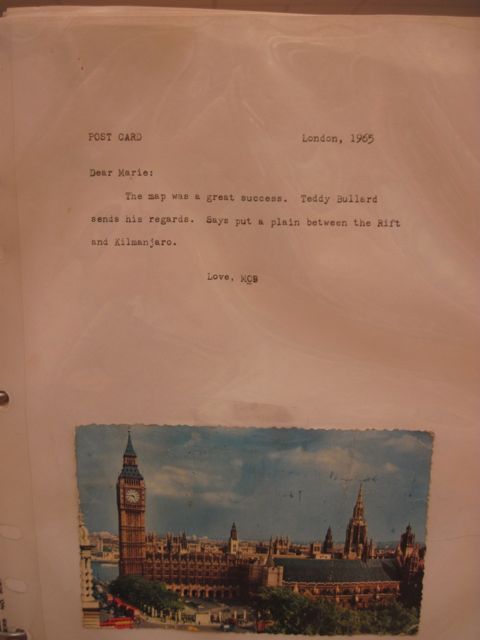

While traveling, Bruce often wrote short notes to Marie on the backs of postcards. During the late 1950s through the 1960s, he signed them “MOB,” which stood for “Mean Old Bastard.” In 1965, Teddy Bullard was one of the world’s most respected geologists; today he is considered one of plate tectonics’ founding fathers.

When I was in high school some of my peers wore bracelets with the letters “WWJD” embroidered on them. I spent a lot of time staring at these bracelets without knowing what the letters stood for−or asking any of my friends (none of whom wore the bracelets) to tell me. But I was daydreamy, and I loved acronyms, so I’d stare and invent possible word combinations: World Wrestling Junior Division? Walruses With Joke Dictionaries? Work With Judicious Dedication? Nothing I came up with seemed capable of inspiring such devotion; this went on for at least six months.

Imagine my delight, then, when I finally discovered what the letters WWJD stood for: What Would Jesus Do? A few seconds of delight, and then…huh, I thought, hmm. I had no context, because except for a couple years when I’d accompanied my aunt and uncle to church so I could get dressed up, I’d mostly been raised a heathen. My daydreaming attention quickly turned elsewhere.

I’m 29 now, and don’t know if high school kids still wear these bracelets, but in the past few years I’ve had occasion to think about them again, putting my own spin on their sentiment when it strikes me. What Would Rachel Maddow Do? I ask myself when I’m trying to be a sharp but funny journalist. When my writing isn’t going so well, and I’m having trouble figuring out how to structure some paragraph or chapter, Joan Didion is the person who comes to mind−what would she do, I ask myself. Lately, though, one person’s name comes up more than the others; What, I ask myself, Would Marie Tharp Do?

Soundings, my biography of Marie, was released a week ago, and in the days leading up to its publication I thought a lot about the responses Marie received when she showed people her early maps. On first glance, her partner, Bruce Heezen, called her revolutionary 1952 discovery of a rift valley on the Atlantic Ocean floor “girl talk.” A few years later, when Marie had traced the rift valley for approximately 40,000 miles across the ocean floor, Maurice “Doc” Ewing, the director of the newly-formed Lamont Geological Observatory (where Marie and Bruce worked), oversaw a press release in which he and Bruce took nearly all of the credit for the discovery; the newspaper articles that appeared as a result followed suit. And when other scientists saw Marie’s initial maps many of them thought that the rift valley was fake, an instance of the young whippersnappers at Lamont trying to be geophysical provocateurs.

In other words, Marie was not lauded. Not in 1952, when she made the discovery that allowed the theories of plate tectonics to be developed. Not in the early 1970s, when these theories began to be included in geology textbooks. Not in 1977, when she finished work on the first complete map of the ocean floor, a map that revealed−for the first time−the 70 percent of the Earth’s surface that lies under the sea. Not in the almost thirty years that she lived after that map’s publication. If you’d endeavored to collect the words written about her by 2006, the year she died, you’d have something like a packet or novella−nowhere near fitting for a scientist who transformed the way we understand the Earth.

But there’s little evidence that Marie was angered by what little recognition she’d received. In fact, during the five years I spent working on her biography, what I saw again and again was a woman who simply didn’t give a damn what other people thought of her. She did her work, and it was important work; people could take it or leave it, but she was always proud of what she had done, she always knew exactly how it had shaped the science that had come after it. What I’m describing, I suppose, is confidence.

Last week I was talking to a friend about how Marie didn’t appear to need external validation; I wished, I told my friend, to be the same. Soundings had come out the previous day, and while it was exciting, it was also kind of anticlimactic: I had known its publication wouldn’t be accompanied by fireworks, but I’d also hoped I would wake up feeling different, that something in me would shift, becoming better or stronger. I’d thought that those things might happen because now perfect strangers could read what I’d worked on for five years. Maybe, I thought, it would be like what some women say happens after they give birth: they see the baby and everything changes. Magically, they are transformed. They become mothers, seemingly in an instant.

Except I don’t think that’s what really happens. I think that’s the moment when the situation becomes real−the baby that was hidden for such a long time is now wailing or staring them in the eye. I’m guessing that’s hard to ignore. But what happens when what you produce has been visible (albeit not in glossy, finished form) for years and years?

When I think about Marie I realize that when the product of years of work has been silently wailing at you for years, you don’t get a single transformative moment. Marie did the bulk of her work during a time that people like her (by which I mean women) had an ice cube’s chance in hell of getting the recognition they deserved; she knew that she would have to be her own main source of validation. I’m fortunate to live in a different time−but I also know that there’s a lot to be said for self-validation. For realizing that publication won’t transform me, that the work was doing that all along, as I learned and read and wrote about what Marie did.

The letter in the image is the 1960s version of a picture-text, isn’t it?

Thank you for writing “Soundings” and this post. There is a lot to be admired in Marie’s attitude towards her work and recognition – both at the start of her career and at the end. If you hadn’t written the book, I would have two fewer female role models to consider.